LAGOS JUNE 25TH (NEWSRANGERS)-In July 2009, reports emerged that security forces had shot dead Abubakar Shekau, the brutal leader of the Nigeria-based terrorist organization Boko Haram. In the summer of 2013, an intelligence assessment claimed a raid in the Sambisa Forest resulted in Shekau’s death. In 2014, the Cameroonian military released photos intended to prove that it had just killed Shekau.

In August 2015, the president of Chad, Idriss Deby, announced his forces had slain Shekau. Almost exactly a year later, in 2016, Nigeria claimed its airstrikes had “fatally wounded” Shekau.

Bring Back Our Girls: The Untold Story of the Global Search for Nigeria’s Missing Schoolgirls, by Joe Parkinson and Drew Hinshaw. Harper, 432 pp., $28.99.

Then, on May 21, 2021, the Wall Street Journal published an exclusive scoop: Boko Haram leader Abubakar Shekau — well, you know the rest.

This time, however, it seems Shekau is destined to stay dead. On June 18, a video from a top Boko Haram religious figure all but confirmed the news.

Shekau’s name was not well known among Americans, but one of his exploits certainly was: the 2014 kidnapping of 276 schoolgirls from the eastern Nigerian town of Chibok. That infamous act, and the role played by social media in making it a global public drama, is the subject of the excellent book Bring Back Our Girls, by Joe Parkinson and Drew Hinshaw, two reporters for the Wall Street Journal.

In addition to writing a gripping account of the tragedy, Parkinson and Hinshaw show the fascinating, if perverse, effects of social media on global conflicts. A hashtag on behalf of the kidnapped students, #BringBackOurGirls, turned into a worldwide online protest movement.

But publicity for captives is a double-edged sword. Understanding why requires a glance at the global kidnapping industry from the terrorists’ perspective. In 2012, then-Treasury Undersecretary David Cohen said that “kidnapping for ransom has become today’s most significant source of terrorist financing because it has proven itself a frighteningly successful tactic.” In the previous eight years, terrorists had collected about $120 million through kidnapping, though the real numbers are probably higher. According to federal government estimates, the Islamic State received $50 million in ransom payments in 2014 alone.

At nearly midnight on April 14, 2014, the students at Chibok Girls Secondary School were ordered out of their dorms. Dozens of bearded militants in flip-flops looted the campus of food and its brickmaker but were disappointed in the total haul. They burned the school buildings and then called an audible, ordering the girls onto trucks. They hadn’t planned on taking the students captive but needed more of a return on their investment to justify the operation. The men looked to the leader of the raid for guidance. “Shekau will know what to do with them,” he said.

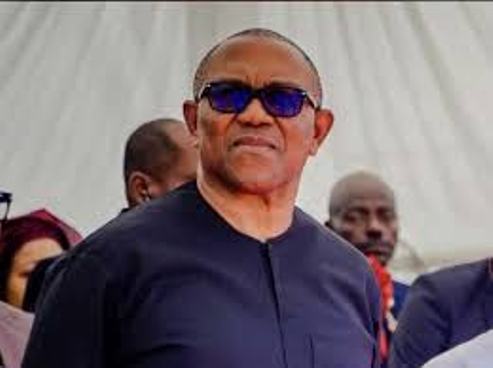

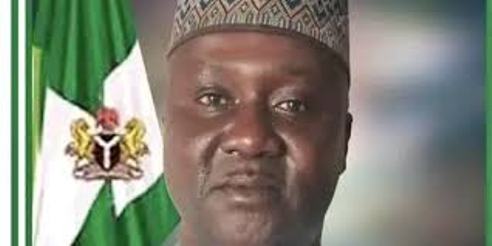

The public campaign to pressure then-Nigerian President Goodluck Jonathan to do more to recover the Chibok captives started in earnest with a woman named Oby Ezekwesili, a former government minister and vice president at the World Bank who left government to rail against corruption. Nine days after the kidnapping, Oby gave a public talk at a book festival and mentioned the Chibok girls. A member of the audience tweeted about it and used the hashtag #BringBackOurGirls. Oby retweeted it, and a movement was launched. About a week later, music mogul Russell Simmons blasted out the hashtag, and it caught fire among Western celebrities. Less than a week after that, a tweet from Hillary Clinton lit the match among political elites. Nancy Pelosi and Tim Scott led a moment of silence at the Capitol for the Chibok girls.

Shekau basked in the attention and egged it on. Privately, then-President Barack Obama had authorized national security adviser Susan Rice to help Jonathan find the girls, but the White House was about to take a more public stance: First lady Michelle Obama tweeted a picture of herself holding a sign that said #BringBackOurGirls.

In the air above Nigeria’s dense forests, American drones searched for the kidnappers. On the ground, mercenary bounty hunters and retired soldiers led freelance missions. Swiss mediators and a Dubai-based former Nigerian journalist with sources in Boko Haram teamed up to lead the diplomatic effort to recover the girls.

Shekau had the world’s attention — and a prized bevy of hostages. The target of #BringBackOurGirls, after all, wasn’t Shekau but the Nigerian president. As pressure on Jonathan rose, the value of the hostages soared. The scandal of the kidnapping eventually doomed Jonathan’s reelection campaign against Muhammadu Buhari. In other words, thanks to a Twitter campaign drawing attention to his crimes, Shekau was watching his negotiating position strengthen, building alliances outside Nigeria, and bringing down his country’s president.

About a year after the abduction, Obama promised Buhari that the United States would boost military aid to Nigeria to keep the search alive.

“Into the countries surrounding Nigeria, the Pentagon was pouring hundreds of troops, who were bringing new tactical vests and night-vision goggles to the local soldiers, whom they would accompany on border patrols, in trucks fueled by American funds,” the authors write. “This was the strange and continuing mutation of the #BringBackOurGirls phenomenon. A Twitter hashtag to save schoolgirl hostages had been slowly and covertly morphing into a billion-dollar deployment of drones, intelligence officers, and turboprop planes full of American troops.”

As public attention flagged, Shekau began losing control over his troops. Then in August 2016, over two years after the kidnapping, tragedy struck: An airstrike targeting Boko Haram killed a number of the captives. Swiss negotiators redoubled their efforts, and 21 hostages were freed in return for ransom. The momentum was again crushed by Twitter: “Just after the team had taken off in a helicopter packed with the young women, they checked their phones and saw that a soldier had snapped a photo of them hours earlier, a tweet that was being triumphantly shared by thousands of people unaware that, with a touch of a screen, they were prolonging the other women’s captivity.” Months after the incident, “Boko Haram was still furious over the lapse and refusing to release any more.”

That lasted until May 2017, when negotiators were able to broker the release of 62 more hostages. Over the years, a few escaped, some were forced to marry Boko Haram members, and over 100 are still missing.

Looking back, Michelle Obama’s decision to share a hashtag aimed at shaming an allied country’s president over a terrorist atrocity seems an obvious diplomatic faux pas that arguably helped torpedo her husband’s attempts to help rescue the girls. The hashtag faded from public consciousness, but the troop deployments it inspired remain in the region.

“Many Americans are at best dimly aware that the hashtag they tweeted evolved into some eight hundred troops based in Niger, the Saharan nation to Nigeria’s north, and another three hundred in Cameroon, to the east,” Parkinson and Hinshaw write. “It could be decades before the final deployments of military hardware and manpower are brought home. Officials, senators, presidents, and generals still struggle to make sense of how a group of high-school seniors became the inflection point in which a localized insurgency became a multinational war.”

Seth Mandel is the executive editor of the Washington Examiner magazine.

Washington Examiner